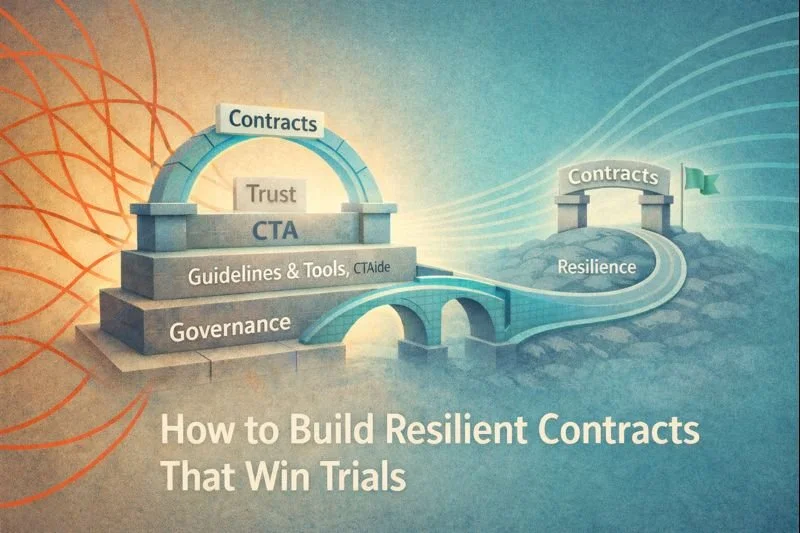

Part 2 - Zero-Redline Thinking: How to Build Resilient Contracts That Win Clinical Trials

The Contracts Manager rose to circulate what looked like one-page flyers he had been guarding closely throughout the meeting. Legal counsel gave him a quizzical look.

He explained that the document was a short-form Clinical Trial Agreement (CTA)—written in plain language, distilled from the company’s standard template and previously executed contracts.

“Is it understandable, flexible, balanced, and usable?” he asked. “Does it cover the essentials—scope, risk, payment, and data rights?”

Legal responded first: the form didn’t comply with company policy, and most sites would never agree to it.

The manager smiled.

“That’s exactly the point,” he said. “If contracts were designed this way—so clear and balanced that no one felt compelled to redline them—we’d eliminate months of negotiation. A CTA now takes three to four months to finalize; an amendment can take an additional one to two months.”

He paused.

“We’re dissatisfied with the quality of our agreements and collaborations—across CROs, labs, technical services, and partnerships. These failures compound.

“Imagine if a design-for-trust template, backed by coherent policies, guidelines, and playbooks, could remove all that pain.”

Silence settled in the room.

Eleanor sensed that the Zero-Redline idea had landed. It was, in essence, a proposal to redesign the contract itself—not as a legal weapon, but as a tool for trust and collaboration.

Why Contracts Fail

Weeks passed after the pre-mortem, and turning insight into an agreed plan proved harder than expected. Approval across departments stalled. The issue eventually reached the executive level, since it implied revisiting corporate policy.

The Contracts Manager’s radical one-page CTA was set aside, but his questions had opened a door.

Teams combed through legacy and active contracts, analyzing negotiation logs and outcomes to trace the roots of failure.

Painful stories surfaced.

In one study, site activation was delayed for weeks—patients waited—because parties couldn’t agree on the indemnification cap. In another, disputes erupted over whether the budget covered unscheduled patient visits.

Patterns emerged.

Key contributors included:

- Disconnect between policy and practice: gaps between stated values and operational reality embedded in SOPs, playbooks, and templates.

- Misaligned priorities: sponsors, sites, and CROs entering negotiations with divergent incentives and expectations

- Imbalanced standard terms: boilerplate clauses perceived as one-sided, prolonging negotiation cycles.

- Lack of clarity in key elements: objectives, scope, logistics, and payment terms left vague or inconsistently applied.

- Inefficient review cycles: repeated drafting rounds eroding trust, momentum, and morale.

- Non-standard handling of sensitive clauses: intellectual property, data ownership, publication rights, and indemnification diverging from accepted norms.

- Overly rigid templates and legalistic language: dense structures discouraging comprehension and systemic problem-solving.

- Poorly aligned incentives: contractual goals failing to reinforce collaboration or shared success.

The conclusion was uncomfortable but unmistakable: the system itself was failing.

Turning Foresight into Action

The pre-mortem revealed that most breakdowns clustered into three systemic categories:

- Governance — policies and contractual frameworks

- Guidelines and Tools — playbooks, negotiation processes, review practices

- Goals and Roles — clarity of objectives, accountability, and performance measures

Contracting could not be fixed in fragments. It required integrated redesign—a cultural and procedural recalibration.

They began with governance. Policies were aligned with ISO 9001 (quality management) and ISO 44001 (collaborative business relationships), establishing a shared language for consistency, transparency, and trust.

Next came tools.

Templates and playbooks were rewritten with a single mandate: make them usable.

The goal was not to simplify the law, but to make legal structure intelligible to those executing it. Each clause carried plain-language guidance explaining intent and risk.

A Contract Review Checklist helped identify red flags early. But to create visibility across studies, they formalized this knowledge into a Clinical Trial Agreement Inventory and assessment tool (CTAide, its digital companion)

Clinical Trial Agreement Inventory provided a structured reference for developing or reviewing CTAs. It maps essential elements—scope, risk, governance, payment, data—and highlights common negotiation pitfalls. It helps reviewers see what is covered, what is missing, and what requires escalation**.

CTAide analyzes agreements for completeness, balance, and usability—flagging clauses that are one-sided or ambiguous. It quantifies risk exposure and visualizes balance across sponsor, CRO, and institution.

Together, these tools turned the Zero-Redline aspiration into something tangible: a trust instrument that could evolve with each negotiation.

In effect, CTAide became a translation layer between human intention and institutional memory—encoding fairness, balance, and precedent into the contracting system itself.

Finally, the focus turned to people.

Policies and tools were necessary, but capability was the multiplier.

Eleanor championed cross-functional training sessions simulating negotiations under real time pressure. The exercises built fluency, empathy, and systems thinking—qualities no software could automate.

“We’re not just contracting faster,” she told the team. “We’re contracting smarter.”

Contracts as the Capstone of Collaboration

Weeks later, Eleanor paused by the watercooler before another program meeting.

A milestone echoed in her mind: forty-five days to site activation; contracts signed on the final day.

The weight was real—and not hers alone.

Even with everything in place, trials could falter.

Yet every failure left traces: a shard of insight into disease progression, a clue to biology’s hidden logic, a refinement of what would not work.

Each study contributed a piece to the Alzheimer’s puzzle.

The contract, she realized, was more than a legal checkpoint. It was both signal and artifact—evidence that trust had been forged and alignment reached.

Like a capstone set atop an arch, it completed a structure that, though fragile, pointed forward.

Beneath that arch lay not just the promise of one therapy, but the shared pursuit of cures yet to come.

She took her glass of water, smiled at the doodle in her notebook—a timeline knocked over by a redline—and felt, for once, that the team had built something resilient enough not merely to endure reality, but to shape it—to give their science its best chance to succeed.

Acknowledgment

CTAide ™ was developed by RHIEOS Ventures in collaboration with Engage Clinical Contract Solutions.

Clinical Trial Agreement Inventory ™ is developed and owned by Engage Clinical Contract Solutions.

Further Reading

Methods and Decision Science

Klein, G. (2007). Performing a Project Premortem. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2007/09/performing-a-project-premortem

Cognitive Bias Lab. Premortem Template and Resources. https://www.cognitivebiaslab.com

Clinical Trial Contracting Tools and Frameworks

Clinical Trial Agreement Inventory and CTAide. https://www.ctaide.com

Dealligence. Collaboration and Negotiation Framework.

Engage Clinical Contract Solutions. Twelve Clinical Trial Contracting Lessons.

Hagan, H. et al. The Contract Design Pattern Library: A Repository of Visually Enhanced, Modular Contract Formats.

Clinical Trial Operations and Start-Up Delays

Getz, K. et al. (2020). Drivers of Start-Up Delays in Global Randomized Clinical Trials. Contemporary Clinical Trials. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7505220/

Miller, J. et al. (2023). Critical Path Activities in Clinical Trial Setup and Conduct: How to Avoid Bottlenecks and Accelerate Clinical Trials. Contemporary Clinical Trials. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1359644623002490

Relational and Collaborative Contracting

Frydlinger, D., Vitasek, K., Bergman, J., & Cummins, T. (2019). Contracting in the New Economy: Using Relational Contracts to Boost Trust and Collaboration in Strategic Business.

Frydlinger, D., Hart, O., & Vitasek, K. (2019). A New Approach to Contracts. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2019/09/a-new-approach-to-contracts

Part 1- Why Trials Falter Before They Begin

Eleanor is energized after her second cup of ristretto. It’s a few minutes before her eight o’clock clinical program-planning meeting — the one that could shape her company’s future and the prospects for patients with Alzheimer’s disease.

As program lead at AlphaBeta Inc., a mid-sized biotech advancing a novel cell therapy for neurological disorders, her team is responsible for both clinical studies and regulatory approval. She’s a drug-development scientist with deep field experience and has seen firsthand the devastating effects of Alzheimer’s and dementia on patients and their families.

A global network of collaborators — medical, clinical operations, finance, legal, hospitals, service providers, patient groups, and more — each holds a stake and a say in the discovery voyage. It’s a daunting challenge — like steering a kayak crew through turbulent waters.

Eleanor’s task seems deceptively simple: design a plan robust enough to meet the board’s ambitious target — three clinical studies in four years.

“It’s a feasible undertaking,” the Chief Medical Officer had said when she asked how the numbers were set.

She nodded, though her stomach tightened. She had seen aspirational targets like this before; they often place crushing pressure on teams and invite mistakes. The ristretto steadied her nerves as she walked to the meeting room.

Study Pre-mortem

Instead of rehearsing hopeful projections, Eleanor’s team turns to a pre-mortem — an exercise in imagining failure before it happens. The idea, developed by cognitive psychologist Gary Klein in 2007, is simple: assume the trial has already failed, then work backward to uncover why.

The method punctures comforting myths. It reveals that what most often delays trial start-ups isn’t contracts or budgets but the overlooked fundamentals — weak protocol design, poor feasibility, hasty site selection, and relationships that were never cultivated.

A Back-to-the-Future View

As Eleanor entered the meeting room, she noticed the Chief Medic and leaders from finance, legal, and HR clustered on one side of the U-shaped table. Opposite them sat the heads of clinical and functional groups — fault lines already visible. Quality and medical experts took up the flanks, ready to tend to any “casualties.”

The mood lightened when Eleanor invited everyone to share a witty line about why the program might fail.

“Every study team has a neat timeline until the redlined CTA punches it in the face,” the Contracts Manager quipped.

“Ouch — I didn’t see that coming,” she said, smiling as the room laughed.

The exercise produced over 130 one-liners, later distilled into a few central themes.

It all begins with the target product profile — the document defining the desired characteristics and therapeutic purpose of the investigational drug. When that profile is incomplete or unrealistic, it ripples through to poor protocol design and limited feasibility, making it hard to recruit eligible patients or sites.

That, in turn, leads to a strenuous path through country-specific regulatory hurdles. Misalignment of goals, priorities, and capabilities among all parties quickly follows. Add in multiple systems and administrative layers, and the mix breeds delays, stress, and preventable mistakes.

Hindsight and Reality Checks

The head of Quality, quiet until now, stood and wrote two words on the flip chart: complex system. He explained that clinical trials, like startups, behave as complex adaptive systems — dynamic, nonlinear, and full of surprises. The room fell silent. Good sign, thought Eleanor.

He launched into a crisp, ten-minute TED-style talk. Silence lingered afterward. Eleanor sensed the CMO wasn’t fully persuaded but had no alternative hypothesis to offer.

“Imagine a loose flotilla of kayakers from different tribes trying to navigate rapids without a skipper,” the Quality head said. “A small shift can upend the entire group — or the entire trial.”

“No wonder more than 90% of studies fail,” someone murmured.

The group moved on to discuss how to avoid those failures.

“We need clear goals with partners — and commitment tied to the right incentives,” said the Chief Medic.

“We must stay adaptable and open in how we work,” added the ClinOps head, smiling wryly.

“Contracts should be tools for trust — where minds, intent, and understanding meet,” said another. “Friction in contracts is often an early warning sign of deeper issues.”

The HR lead added, “We should be as competent in collaboration as we are in negotiation.”

Eleanor concluded: “We learn fast, surface risks early, and dedicate resources to fix them.”

Around the room, heads nodded.

Contracts: Trust Handrails not straitjackets

Contracts are the final step before a trial can begin. Yet long before formal negotiation starts, deal-making is already underway — budget discussions, staffing debates, early talks with investigators, and informal understandings with regulators, sites, and CROs.

Even when nothing is yet signed, expectations may have been set. So the later back-and-forth between legal teams and the drawn-out budget haggling should surprise no one; they often reveal gaps in trust and understanding. When sponsors, sites, and CROs can’t find common ground, the discord tends to echo through every subsequent stage of the study.

Precise language on standard provisions is necessary, but collaboration thrives in the spaces between the words and numbers — in shared intent, transparency, and goodwill.

And even when trust flows freely and contracts function smoothly, studies can still fail: too few patients enroll; endpoints fall short; safety concerns outweigh benefits; or biology simply refuses to cooperate. Eleanor knew all this.

But as the team sat around the U-shaped table, sketching out what might go wrong, she felt a cautious hope. They were, at last, beginning to name the real risks.

In the next part, we’ll follow their journey to design a system built to survive that uncertainty — the Zero-Redline approach.

Copyright. 2025. RHIEOS Ventures Production in collaboration with Engage CCS

Of Sunshine and Patient Access: Solving for “Zero Financial Burden” in our Clinical Research-to-Care Enterprise

By Larry Ajuwon

More than ever, we — patients, care providers, drug developers, payers among others — are all participants in the new drug development and clinical research-to-care paradigm. As the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated, the enterprise was propelled into the unknown at warp speed and patients became much more directly involved as participants in efforts to address the crisis. At the same time, clinical research has continued to evolve as the scientific understanding of disease biology deepens and promising treatment options with new modes of action (MOA) are discovered and developed.

There is growing awareness that clinical research can be considered as a care or treatment option 1 for patients with rare diseases, cancers, and deadly infections where no suitable interventions are available. Payers are also pushing for reimbursement models 2 which are based on patient-reported outcomes in real-world settings. In addition, new digital health technologies are enabling the use of decentralised approaches 3 for both clinical trials and patient care.

In theory, the use of decentralised methods has the potential to expand access for patients but also leads to study designs and protocols becoming more complex owing to additional risks and requirements 4 around things like data privacy, data quality and patient support/outreach.

In many cases, patients are faced with bearing the financial risk and burden 5 associated with study participation.

The confluence of these factors including the relationship between ethics of clinical research and compensation practices recreates a dynamic that limits access and results in a low representation of underserved populations. This lack of diversity also leads to poor enrollment and patient retention, which has a direct impact on the quality of the clinical findings that are produced and could otherwise influence clinical practice and patient care.

Regulatory bodies and industry are now collaborating to drive patient-focused drug development and they have launched various initiatives (see below) to transform different aspects of the process.

At this pivotal moment, addressing the issue of economic and financial burdens with candor to achieve wider patient access across all disease areas and geographies is critical.

Valuing financial burden

A pressing question for all stakeholders in the pharma/life sciences sphere is “Why and how to achieve zero financial burden in clinical research?”

That is the question we pondered during a recent conversation with a veteran industry leader, whose company offers a technology platform for running decentralised clinical trials. The heart of the matter is: “How does this novel approach benefit patients, sponsors, payers, and society at large?”

We postulated the value derived from this construct would:

1) Allow more people to participate in clinical research — hence, helping to address persistent barriers that undermine objectives related to access and diversity.

2) Give investigators greater assurance that patients’ economic well-being is being supported and key ethical issues are being addressed.

3) Allow money spent by sponsors to satisfy the study objectives — and help to enable the effective use of capital/resources.

This new paradigm — which considers the economics of the patient burden — seems to offer plenty of opportunities for making the system more effective and efficient but there is no global standard, framework, or method for calculating the amounts that patients may receive as compensation or remuneration. 6

At the local community, state, and national levels, there are many practices, and norms regarding financial compensation, from providing fixed stipends to covering patient travel expenses (or reimbursement for such expenses), and/or offering compensation for time and effort to providing nothing at all. For example, stipend compensation is more common in the US.6

This compares with direct travel cost reimbursement in most EU countries, time/effort payment in Sub-Saharan Africa 8 and SE Asia 9 and some travel cost in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA).

Some studies10 have shown that compensating patients improves trial enrollment, and patient retention, along with increased access, however, we think such measures are useful as a by-product of the process and will provide data and insight to deepen our knowledge of socio-economics, medical research, and health.

Medical and research ethics (From Ancient Egypt to Helsinki)

In trying to figure out a budget line item to estimate the cost of a patient’s burden using minimum hourly wage to devise an ethical compensation formula that does not leave patients short-changed, the search led us, unexpectedly, to the 5th Egyptian dynasty (24th century BC) when the Nenkh-Sekhmet, chief of the physicians, had what is considered the first recorded medical ethics code on his tomb.

'Never did I do evil towards any person’ 11

As a precursor to the Hippocratic Oath of “First Do No Harm,” this principle is enshrined in later medical ethics codes including The Principles of the Declaration of Helsinki,12 the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS), 13 and The Belmont Report, 14 all of which mandate the protection of a patient’s rights, dignity, and well-being.

In clinical research, well-being would cover such things as ensuring patient safety, defining an acceptable risk-benefit ratio, and limiting the burden (including physical, psychological, and socioeconomic burden) to which participants will be exposed.

If our collective vision is to attain health equity, which the World Health Organization (WHO) defines as achieved when everyone can attain their full potential for health and well-being,15 then it seems our “simple task” as a research-to-care enterprise is to ensure that we keep to our ethical foundational principles constant.

Can industry and society support this ideal by enabling everyone to have access to research opportunities as a care option without experiencing the adverse effect of financial toxicity16 or economic distress?

Today’s industry enablers and trends

Real-world evidence (RWE) and outcomes contribute to marketing authorisations and influences reimbursement decisions

Underserved groups are traditionally underrepresented in clinical trials17 due to several factors including the risk of loss of income. This has broader implications in that approved treatments may not be demonstrated to be effective in these populations in real-world settings, leading to poorer health outcomes. Now that reimbursement decisions by payers are increasingly directly linked to how well the treatments are performing in the real world, sponsor organizations will be putting forecast incomes at risk, if pivotal studies do not include adequate patient representation that will in turn produce representative data.

Patients are engaged as partners in drug development and evaluation.

The patient-focused drug-development approach18 — supported by conscientious engagement efforts by regulatory bodies, industry, and patient advocacy groups — is increasingly being embraced, with the primary goal of better incorporating the patient voice into drug development and evaluation.

Over the last 10 years, patients and patient groups have been playing a bigger role in the clinical research enterprise through expanded patient-engagement initiatives, such as consulting patients on clinical study design, usability testing of information materials,19 and contributing to protocol development.

The National Health Council (NHC),20 the Patient Focused Medicines Development, 21 and the European Patients’ Academy (EUPATI)22 are developing principles, practices, and patient compensation tools including having a fair market value (FMV) fee calculator, remuneration framework, and activities under a cross-industry initiative.

To go from being labeled subjects (the patients) to becoming partners in the healthcare ecosystem is a vital consideration.

The COVID-19 pandemic expanded clinical research and accelerated new operating models

The intense search for COVID-19 treatments resulted in a 7% increase in the number of new trials registered on the Clinicaltrials.gov 23 database for the period 2020–2022 (111, 781) compared to the previous period 2017–2019 (92,646). This later period also saw the rapid adoption of decentralization models in which studies involved having patient visits and assessments conducted remotely or at home.

Between 2015 and 2019, the studies averaged approx. 50,000 trial participants per year globally based on analysis of the FDA Drug Trials Snapshot Report.24

One large global contract research organization 25 also reported that perhaps owing to COVID-19, for the first time in 2021, the aggregate number of study participants intended for new trials was expected to exceed 2 million, double the level seen before the trials for both COVID-19 and several very large Ebola virus vaccine trials.

That is a 40-fold increase in two years!

In addition, the emergence of new digital tools and technologies (such as telemedicine, mobile health applications, home health services, patient-reported outcome tools, and more) that support decentralisation objectives are designed to broaden access to clinical trials and improve patient diversity.

Solving for zero financial burden in clinical trials

Navigating the path forward — A few recommendations

The COVID-19 pandemic has redirected drug development and healthcare enterprises onto a new path and has also energized stakeholders to make changes to meet the challenges of the new global health reality. To help keep up the momentum, the following are some aspirational goals that we propose:

1. Patient: Agree to financial arrangements in which all costs resulting from participation are covered with no risk of incurring loss in the future.

2. Patient advocate: Assign a patient financial advocate to all trials to help ensure that an adequate budget is earmarked and each patient undergoes an economic health check to ensure that adequate support is provided.

3. Openness: Adopt the “Sunshine Act Principle” reporting code for patient payments to ensure transparency and bench-marking at the national, regional, state, and local government levels.

4. Ethics Review - Decision-Making Framework/Policy: Standardize and publish a framework and make it subject to periodic assessment by an independent body.

5. Adequate coverage: Provide economically viable way for standard-of-care charges, insurance payments etc., to be covered under special “clinical research-to-care” plans/schemes.

6. Informed Consent (IC): Specify financial compensation arrangements (such as minimum stipend and other payments) in consent forms and publish it on all primary clinical trials registries. (eg, EU Clinical Trials Register, Clinicaltrials.gov, Japan Primary Registries Network).

7. Fair Wage Value: In determining the appropriate remuneration decision method and amounts, use the average country/region hourly wage based on International Labour Organization (ILO) data, adjusted for purchasing power parity (PPP).26

Parting thoughts…

As the conversation with the veteran industry leader draws to a close, we both agreed to share two take-away actions: the first was to help focus more attention on this topic in our respective communities, and, the second, was to explore how we can build an open data-sharing platform together with all participants to steer having clinical research as a care option toward a more equitable and burden-free future for all patients. Q.E.D

©

Larry Ajuwon is the Founder and Director of RHIEOS, a clinical innovation consultancy focused on enabling better access to treatments and lowering barriers to building viable health systems. Email: lajuwon@rhieosventures.co.uk

Acknowledgements

My gratitude goes to many people (colleagues, friends, clients, researchers..) who have contributed in one way or the other to the writing of this essay. In particular, the insights shared by and discussions with the following people have encouraged bold thinking on the topic and enriched my perspective.

Kamila Novak, excellent article highlights the different payment practices across the world and makes a good case for improvement and review.

Eric Nier, we had an informative conversation on how technology is being used to simplify patient payments and reduce financial burden

Kimberly Richardson et al shared some insights during this roundtable discussion

Gunnar Esiason makes a good case for better pay and patient advocacy in this article

Suzanne Shelley provided valuable editorial assistance and critique during the drafting

Sources

Virtual Clinical Trials: Challenges and Opportunities: A Workshop

Decentralized clinical trials (DCTs): A few ethical considerations

Fair payment and just benefits to enhance diversity in clinical research

Clinical trial participant time, inconvenience and expense (tie) compensation mode

The Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS)

Definition of financial toxicity

Improving Representation in Clinical Trials and Research: Building Research Equity for Women and Underrepresented Groups https://nap.nationalacademies.org/resource/26479/CT_Highlights.pdf

Practices of patient engagement in drug development: a systematic scoping review

“our “simple task” as a research-to-care enterprise is to ensure that we keep to our ethical foundational principles constant”